This program celebrates the recent efforts made by Brooklyn Museum to preserve its audiovisual collection. Featured here are two newly digitized works, including a 1937 nitrate film shot on the streets of Brooklyn and a 1962 film on art conservation. While the keeping of juridical paper archives has been instinctive to societies for millennia, the preservation of film languished for much of its early history. It was not until cinema’s legitimization as an art form and the founding of institutions like the British Film Institute, Museum of Modern Art, and Cinémathèque française that this blight in our culture and history began to be amended.

However, film also occupies a place outside of artistic canons. Peter Delpeut, along with computer artist Hoos Blotkamp and filmmaker Eric De Kuyper, created a new collection policy in the 1990s during their tenures at the Nederlands Filmmuseum. Their endeavor coincided with film historiography’s growing concern for endangered films and led to the creation of the “Bits & Pieces” collection. This collection comprises fragmented films that are neither eminently related to auteurs nor formal artistic movements. As a director, Delpeut made his name as a found footage filmmaker who appropriated such fragments. He represents something of a progenitor to artists like Gustav Deutsch and Bill Morrison, with his film Lyrical Nitrate preceding the latter’s Decasia by a decade. For Delpeut, the derogatory idiom which describes history as an “ash heap” or a “dustbin” rings untrue. He has described his work from within the archive as the most emotional period in his film-related life. It is this emotion which he shares with his audiences by wresting images of surprising beauty and pathos from their obscurity and neglect.

This program of three screenings featuring the films of Brooklyn Museum, Peter Delpeut, Harun Farocki, and Mark-Paul Meyer honors art conservators and archivists. Prelude short films demonstrating conservation techniques like vacuum hot tables and wet-transfers are at once educational and beautiful. The craquelure of oil paintings and the decomposition of film which these technical interventions intend to remedy introduce a sense of biological infirmity to the cultural heritage which we often presume to be immutable and everlasting. The feature length films of this program explicitly address art and build on the related motifs of transience and materiality in different ways, ranging from Delpeut’s lyrical lamentations to Farocki’s capitalist critique.

We would like to thank Video Data Bank and Eye Filmmusuem as generous contributors to this program.

PETER DELPEUT AND THE ASH HEAP OF FILM HISTORY #1

Sunday, October 3 – 5pm

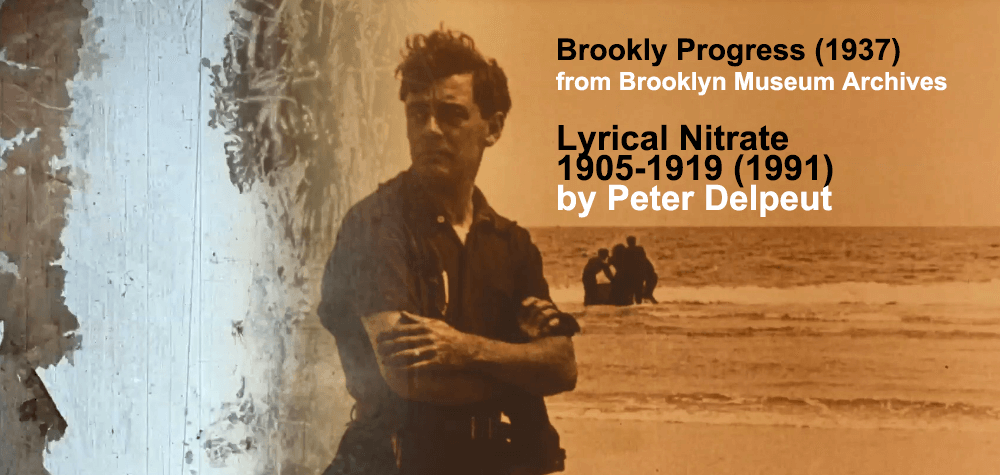

BROOKLYN PROGRESS

1937.

10 mins. United States.

LYRICAL NITRATE 1905-1919

dir. by Peter Delpeut, 1991.

51 mins. Netherlands

Brooklyn Progress is a nitrate film whose original camera negative was discovered in Brookyln Museum’s audiovisual collection by archivist Molly Seegers in 2016. In a serendipity not unlike the discovery of Japan’s oldest negative film – which was until recently under the continuous care of a toothpaste corporation – the archive has transformed a petty propaganda film otherwise lost to time into a precious artifact which displays in verité a burgeoning Brooklyn from nearly a century ago. Originally created for Borough President Raymon V. Ingersoll’s re-election campaign, Brooklyn Progress takes a tour of the achievements of his administration through the eyes of two ordinary citizens as they walk through the city’s streets. The only other extant physical copy of the film is held by the Museum of Modern Art. The Brooklyn Museum negative has since been preserved, digitized, and deposited in the Library of Congress.

Lyrical Nitrate 1905-1915 is a found footage film by Peter Delpeut comprising fragments of the Jean Desmet Collection, which was the first film collection to be selected by UNESCO for the Memory of the World Register. In the context of the Nederlands Filmmuseum’s preservation work and the often repeated adage of “Nitrate Can’t Wait,” Lyrical Nitrate is a nostalgic lamentation for material fragility and the irrevocably lost. It registers both the euphoria and pathos which the images of the past invoke in their variable states, whether silent, scored, tinted, toned, whole, or fragmented.

PETER DELPEUT AND THE ASH HEAP OF FILM HISTORY #2

Sunday, October 17 – 5pm

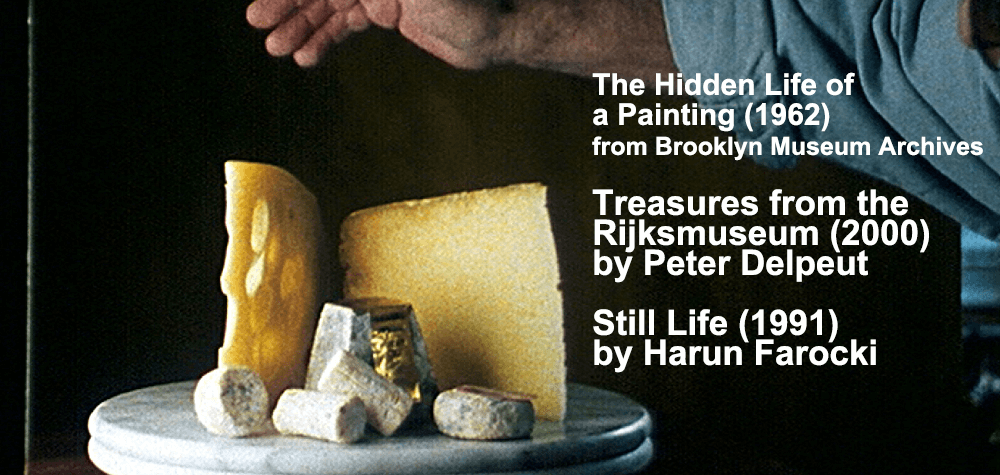

THE HIDDEN LIFE OF A PAINTING

dir. by Caroline Keck, 1962.

20 mins. United States.

TREASURES FROM THE RIJKSMUSEUM

dir. by Peter Delpeut, 2000.

48 mins. Netherlands.

STILL LIFE

dir. by Harun Farocki, 1991.

56 mins. Germany.

The Hidden Life of a Painting was produced by two pioneer conservators during the Exposition of Painting Conservation held at Brooklyn Museum in 1962. With great mid-century charm and a degree of self-effacement, narrator and director Caroline Keck relays the ordinary and surprising ways artworks are preserved and cared for through the use of microscopes, fire extinguishers, polarizing screens, vacuum hot tables, and x-rays. The film concludes with a loaned painting being packed in a crate addressed to Amsterdam.

Peter Delpeut picks up where the Kecks left off and takes us to Holland. Although Treasures of the Rijksmuseum deviates from the found footage works for which Delpeut is most well-known, it elaborates on the same themes of history and materiality. Dust gathers in art depots and the mise-en-scène of the museum requires careful coordination from light technicians and art handlers. The film comes together like a choreography –a wordless homily on the assiduous labors of museum staff and a mediation on their measured movements as they prepare paintings for public display, including Rembrandt’s monumental The Night Watch.

Harun Farocki approaches art materiality with a different kind of emotion by drawing a parallel between the Flemish and Dutch traditions of still life painting with modern advertising. Still Life follows two painstaking photoshoots for a beer and wristwatch advert, the hypnotic mundanity of which can ascend to reverie and perverse delight. A sentiment that is likely shared by the other filmmakers in this program, Farocki states that “when you look at things, the men who made them are unimaginable.” Still Life may either convince us to look at advertisements with a renewed aesthetic acuity or to scrutinize the capitalism and crude systems of patronage undergirding the history of art. Continuing the themes present in much of his oeuvre, Farocki strives to scrutinize a fundamental aspect of our increasingly visual culture by critically examining the ontologies of the image.

PETER DELPEUT AND THE ASH HEAP OF FILM HISTORY #3

Sunday, October 24 – 5pm

OUR INFLAMMABLE FILM HERITAGE

dir. by Mark-Paul Meyer, 1994.

20 mins. Netherlands.

FORBIDDEN QUEST

dir. by Peter Delpeut, 1993.

70 mins. Netherlands.

Our Inflammable Nitrate Heritage is a short film directed by Mark-Paul Meyer, who is presently the Expanded Cinema Curator at Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. Using the restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1918 Meyer aus Berlin as an example, the film shows the time-consuming and complex work processes which allow film archivists to make the best possible copy of a deteriorated film. Although commissioned by the Cineteca del Comune di Bologna and intended for pedagogical value, Our Inflammable Nitrate Heritage is also a visual delight partaking in the same grace and process-oriented hypnosis of Peter Delpeut’s Treasures from the Rijksmuseum and Harun Farocki’s Still Life.

While the wet-gate transfer demonstrated in Our Inflammable Nitrate Heritage is one of the most indispensable techniques in bringing clarity to old images, the motif of water takes on a sense of mystery and icy opacity in Peter Delpeut’s second feature film Forbidden Quest. This mockumentary presents the reflections of the only survivor of a secret South Pole expedition, who is played by the great Irish stage actor Joseph O’Connor. The archival footage used to illustrate this fictional expedition was shot in precarious, real-life conditions in the first three decades of the twentieth century by cameramen such as Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, to whom this film is dedicated. Their images assume a shade of horror and foreboding with a storytelling reminiscent of Verne, Melville, and perhaps even H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness. The visages of people and animals against the backdrop of an inhospitable, unchartered territory are presented in silence. As audiences, we confront film as a ghostly indexical trace to the past and contemplate the enormity of the Shakelton Journey and the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.