By 1968, Spain saw a slight relaxation in the film censorship laws enforced under Francisco Franco’s dictatorship. This allowed films like THE HOUSE THAT SCREAMED (1969) and THE MARK OF THE WOLFMAN (1968) to be produced; the former, despite being cut in Spain, became the highest-grossing Spanish film of its time.

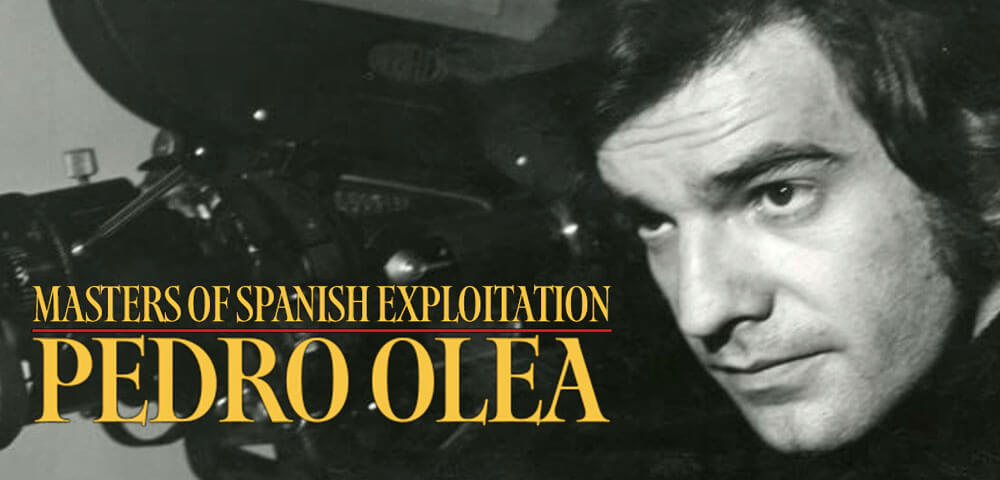

The success of these films marked the beginning of the golden age of Spanish B-movie horror, known as “Fantaterror” (a term coined by MARK OF THE WOLFMAN star Paul Naschy). In his essay Fantaterror: Gothic Monsters in the Golden Age of Spanish B-Movie Horror, 1968-80, Xavier Aldana Reyes writes that “Fantaterror was … the Spanish answer to the type of violent and titillating films that have come to be known as ‘exploitation cinema’ within the European and American contexts.” Some directors from this wave have garnered acclaim and renewed interest among genre enthusiasts, such as Jesús Franco, Amando de Ossorio, and Narciso Ibáñez Serrador. But many others remain largely unknown, like Pedro Olea.

Olea directed his first feature, the musical DAYS OF OLD COLOR, in 1968 before venturing into horror with arguably his most well-known film, THE FOREST OF THE WOLF (1970). Unlike many of his contemporaries, who relied on gore to frighten audiences, he adopted a more reserved and surreal Kafkaesque approach, partly to appease censors. In an interview with Nuestro Cine, Olea remarked that his horror was “more indirect, subterranean, more through the tone of the films than the concrete situations they reflect.” This thoughtful approach blends a foreboding atmosphere with themes of isolation and morality, evoking profound dread. That emphasis on nuance makes Olea a unique voice in Fantaterror.

This March, Spectacle proudly presents three of Olea’s best works: THE FOREST OF THE WOLF, THE HOUSE WITHOUT FRONTIERS (1972), and IT IS NOT GOOD FOR A MAN TO BE ALONE (1973).

THE FOREST OF THE WOLF

(EL BOSQUE DEL LOBO)

(THE ANCINES WOODS)

Dir. Pedro Olea, 1970

Spain, 90 min

In Spanish with English subtitles

MONDAY, FEBRUARY 3 – 7:30 PM

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 12 – 10 PM

MONDAY, FEBRUARY 17 – 10 PM

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28 – 7:30 PM

Benito Freire is a peddler who roams from village to village, selling his wares and delivering messages. Convincing himself he is a werewolf, Benito lures unsuspecting victims into the woods under the pretense that they’re needed in neighboring villages, leaving their families none the wiser. The film is based on a novel by Carlos Martínez-Barbeito that loosely fictionalizes the exploits of Spain’s first serial killer, Manuel Blanco Romasanta, who claimed he was not responsible for his murders because he was a werewolf.

During production, Olea was forced to tone down the film’s violence and redact much of its religious iconography to appease censors, who still condemned it for its perceived anti-religious themes. Admiral Carrero Blanco even attempted to ban the movie following a private viewing, highlighting the contentious relationship between filmmakers and the Spanish state during this period. Despite the cuts, Olea masterfully crafts an eerie world steeped in superstition. The film has garnered renewed interest amid the folk horror resurgence of recent years, thanks to its woodland setting, themes of isolation and manipulation, and exploration of legend and religion.

THE HOUSE WITHOUT FRONTIERS

(LA CASA SIN FRONTERAS)

Dir. Pedro Olea, 1972

Spain, 92 min

In Spanish with English subtitles

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7 – MIDNIGHT

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 15 – 5 PM

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 23 – 5 PM

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28 – MIDNIGHT

After moving to Bilbao in search of work, Daniel is approached by a member of the elusive organization known as the House Without Frontiers and tasked with tracking down one of its deserters. If he fails, he will face “The Only Penalty.”

Even with its anti-totalitarian themes, THE HOUSE WITHOUT FRONTIERS managed to evade Spain’s stringent censorship and was released uncut just three years before the end of Franco’s dictatorship in 1975. This is particularly remarkable given the parallels between the House Without Frontiers and the real organization Opus Dei, explored in Jorge Pérez’s Confessional Cinema: Religion, Film, and Modernity in Spain’s Development Years, 1960-1975. Pérez writes: “These activities appear to echo the hard-line proselytizing that Opus Dei members are compelled to carry out and the harsh treatment of dissenters and dropouts.”

One possible reason THE HOUSE WITHOUT FRONTIERS escaped censorship was the decision to refrain from referencing Opus Dei in the marketing. Additionally, the censorship board didn’t believe the movie would have enough appeal to reach a wide audience, despite its (unsuccessful) campaign to be Spain’s submission for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Unfortunately, this proved correct, as the film flopped and faded into obscurity. Even today, THE HOUSE WITHOUT FRONTIERS remains largely underseen, often overshadowed by thematically similar Italian films like SHORT NIGHT OF GLASS DOLLS (1971) and ALL THE COLORS OF THE DARK (1972). But with its haunting cinematography and strikingly decrepit locations in Bilbao, it deserves critical reexamination.

IT IS NOT GOOD FOR A MAN TO BE ALONE

(NO ES BUENO QUE EL HOMBRE ESTE SOLO)

Dir. Pedro Olea, 1973

Spain, 88 min

In Spanish with English subtitles

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 4 – 10 PM

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 9 – 5 PM

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20 – 10 PM

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28 – 10 PM

Martin loves his wife Elena very much. He combs her hair, cooks her meals, and never leaves her side. The only problem is that she’s a mannequin. When the neighbor’s daughter discovers this dark secret, Martin’s world begins collapsing.

It’s no surprise that IT IS NOT GOOD FOR A MAN TO BE ALONE was shot down when submitted to censors, what with its critical commentary on the patriarchal structures of late Francoist society. During the early ’70s, more women joined the Spanish workforce and feminists fought for change. Olea’s thought-provoking narrative explores the complexities of loneliness and the construction of gender roles amid this transition to a more progressive future.

IT IS NOT GOOD FOR A MAN TO BE ALONE wasn’t released until five years after its completion. While it was in limbo, LIFE SIZE, another film about a man obsessed with a mannequin, came out in Spain in 1974. LIFE SIZE’s popularity and notoriety overshadowed this one, but Olea’s film is more poignant and compelling.