(This event is $10.)

ONE NIGHT ONLY! GET YOUR TICKETS!

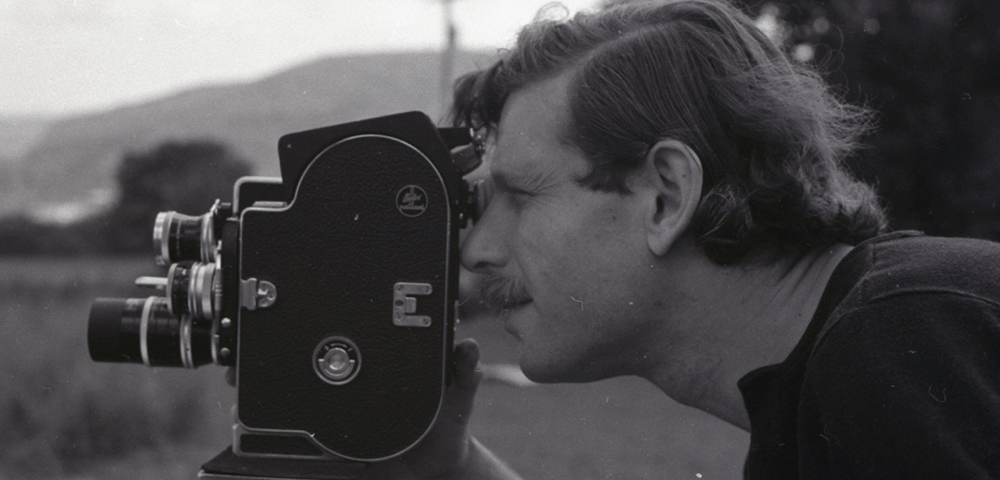

One of the fundamental figures of American avant-garde cinema, LARRY GOTTHEIM has composed a diverse body of work over the span of 50 years. His films stretch the boundaries of cinema as a vessel for deeply personal and philosophical expression and explore the rich blurred zone between the life of the mind and the material world. In 1967, Gottheim founded the Cinema Department at Binghamton University, which was the first regular undergraduate program that dealt with cinema as a personal art, bringing along key avant garde filmmakers like Ken Jacobs and Ernie Gehr as faculty. Considering the theme of nature in art and functions of racial, cultural and personal identity, Gottheim’s practice explores the ways in which time, movement, and becoming are bound up in a complex relation between formal cinematic patterns and pro-filmic subjects. In the beginning is the ending. (All film descriptions written by the artist.)

BLUES

1969. 8 ½ mins. 16mm at 16fps.

“A close continuous view of a bowl of blueberries and milk. A spoon comes in and scoops up some of the berries, presumably to be eaten, until they are all gone. The milk, that is always there, manifests itself more and more as the berries are removed and finally seems to rise up and be washed over by light that struck the end of the camera roll as it was removed from the camera. A malfunction with the camera motor of a rare 8mm Bolex produces a regular pulse against the slight flicker of the shutter at silent speed. There are already indications of a mystery as some of the berries move down as though charged by the energy of the camera’s and viewer’s concentration. This is my first real film; all the others rise out of this one.”

CORN

1970. 11 mins. 16mm.

“This is one of the films that came out of a rejection of expressive camera work, sound, language, editing. I wanted to offer a rich experience of phenomena and associations that could come from a continuous moving image the length of a roll of film. The scene is a space of ceremony, of an offering. This is the world of my house in the country, of my marriage to a potter whose bowl represents her. She is the actor. There are actions that have to do with the transformation of ears of corn into sustenance. These actions take place within a space/time theater of slow continuous changes of light and shadow. There are long spaces where the viewer is free to look at various parts of the screen and, with the steam that rises from the cooked ears, into the very grains of the film itself. The sinuous dance of steam is a counterpart to the fog of FOG LINE. The two films are joined.”

DOORWAY

1970. 7 ½ mins. 16mm at 16 fps.

“Finally I moved the camera, in a slow pan from one side of the wide door of my wife’s pottery studio to the other. While the camera is panning left, the visual sense is of the features of the near and far landscape moving right. The doorway itself marks a plane separating the inside from the outside, as windows will do in other films. Because of the change in temperature between the inside and outside there is a pulse that is visible along with the shutter’s pulse when the film is projected at the correct silent speed. This pulse seems like the pulse of vision that emanates out from the camera, making a moving cow stand frozen behind another. That image stands out from the other material as most charged with meaning, but it too passes by. The lines of hills and fences end edges continue the motif of the line in FOG LINE, and prefigure HORIZONS.”

THOUGHT

1970. 7 ½ mins. 16mm at 16 fps.

“The last of my continuous shot silent films. There is a very limited field of view, with small sliding and focus motions, but a lot to see. The previous films grew out of formal ideas, without much conscious concern with meaning, but now I was becoming aware of the implications of these works, and so I gave it this title.”

HARMONICA

1971. 10 ½ mins. 16mm.

“This concludes the series of continuous shot films, but now with sound. The sound is produced by the car and the people inside it. The car window is both a screen and a plane that separates the inner world from the outside. Shelley, the performer, generates the primary sound when he breaks through that plane. The film is popular because of the vibrant energy of the performer, the music, and the autumn landscape, but it is also complex. As with the previous films, I myself am passive. The driver and the car and Shelley are the creative forces. He is the first of many avatars, doubles of me, that appear in many of my films and that became one thread of my later attraction to ceremonial possession.”

KNOT/NOT

2019. 22 mins. Video.

‘“KNOT”—wrapping things up, tying things up. “NOT “– cross out, erasure. Material from a documentary about conductor Wilhelm Fürtwangler, material from a graffiti stencil work on a brick wall near where I live, a stencil of a girl writing something on the wall, what she wrote crossed out by another act of graffiti. These are the main elements. Also footage looking down at the water of Pearl Harbor with the ruins of battleship Arizona beneath. It had turned red with age. And some footage from Manchester the morning after the terrorists struck. All composed against a sound piece, a multiplication table repeated in four languages. Everything superimposed. It’s not just about what it’s about, but also memory, negatives that try to get negated. About music and painting. Politics, longing and regret. Superimposition is the primary device. The doubling and tripling suggest many implications.’

Special thanks to Malkah Manouel, Christian Flemm and Phil Coldiron.