To mark the conclusion of Spectacle’s fourth full calendar year of operation, our programming collective has selected their favorites from among the regular series features each other showed throughout the past twelve months. The result, BEST OF SPECTACLE (aka BoS2K14), provides an opportunity to revisit some of 2014’s greatest discoveries, thrills and audience-pleasers. This is the first half of our selections, stay tuned for the second half coming in January!

As the year draws to a close, Spectacle would like to acknowledge the audiences, artists and distributors who have pitched in their support, vision and feedback. Thank you for another brilliant year! We’ll save you a seat in 2015.

DIVORCE IRANIAN STYLE

Dir. Kim Longinotto and Ziba Mir-Hosseini, 1998

Iran/England, 80 min.

In Farsi with English subtitles.

MONDAY, DECEMBER 1 – 7:30 PM

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 9 – 10 PM

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 14 – 5 PM

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 20 – 7:30 PM

Part of the Three Films by Kim Longinotto series. Special thanks to Women Make Movies!

Hilarious, tragic, stirring – this fly-on-the-wall look at several weeks in an Iranian divorce court provides a unique window into the intimate circumstances of Iranian women’s lives. Following Jamileh, whose husband beats her, Ziba, a 16-year-old trying to divorce her 38-year-old husband, and Maryam, who is desperately fighting to gain custody of her daughters, this deadpan chronicle showcases the strength, ingenuity, and guile with which they confront biased laws, a Kafaka-esque administrative system, and their husbands’ and families’ rage to gain divorces.

With the barest of commentary, acclaimed director Kim Longinotto turns her cameras on the court for a subtle, fascinating look at women’s lives in a country which is little known to most Americans. Directed by Kim Longinotto and Ziba Mir-Hosseini, author of Marriage on Trial: A Study of Islamic Family Law.

“A fascinating verite-style documentary that counters with compassion, humor, and a keen nose for spotting empathetic characters, strong-willed women, and dramatic moments, the traditional stereotypes of women in the Muslim world as passive victims.” – Hamid Naficy, Author, ‘The Making of Exile Cultures: Iranian Television in Los Angeles’

EXTREME PRIVATE EROS: LOVE SONG 1974

Dir. Kazuo Hara, 1974

Japan, 98 min.

In Japanese with English subtitles.

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 2 – 10 PM

MONDAY, DECEMBER 8 – 7:30 PM

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 20 – 10 PM

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 23 – 7:30 PM

Part of The Bitter Truths of Kazuo Hara series. Special thanks to Tidepoint Films.

Shot over several years, EXTREME PRIVATE EROS: LOVE SONG 1974, a documentary about Hara’s ex-lover was a clarion call against a historically reserved Japanese culture. The film follows Miyuki Takeda, Hara’s ex and father of his son, as she navigates new relationships (first with a woman, and then with an American GI in Okinawa), raises her son, and explores life in 1970s Japan as an outspoken feminist. But the film isn’t just a portrait of the vulnerabilities of a radical feminist single mother, in a time when that wasn’t heard of; Miyuki often takes the opportunity of being filmed by her ex to let loose with what she really thinks about him as a partner, as a lover, and as a filmmaker.

As well as a portrait of two complicated, damaged people, the film is a portrait of Okinawa as a dysfunctional city, damaged by two decades of American military presence. Hara films the GI bars and the underage prostitutes that frequent the bars for business. Hara takes a detour into the life of a 14-year-old “Okinawa girl” Chichi, whose life converges and diverges from Miyuki’s story in intriguing ways.

Released around the same time as the groundbreaking PBS series An American Family (and predating the similarly-themed SHERMAN’S MARCH by a decade), EXTREME PRIVATE EROS takes a long, hard look at gender roles, romantic relationships, and what it means to be a family in 1970s Japan. Hara’s out-of-sync sound and hand-held photography are disorienting and intimate at the same time, giving the feel of an experimental film to a film with very real content. The results are bitter and sometimes hard to watch, but always compelling.

THE FALLS

Dir. Peter Greenaway, 1980

UK, 195 min.

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 18 – 7 PM

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 21 – 5 PM

A sprawling science fiction microbudget epic, Peter Greenaway’s THE FALLS is one of the more successful experimental features in accessibility and one that lasts 3 plus hours to boot. Known as Peter Greenaway’s favorite film of his own work, THE FALLS goes through a catalog of 92 individuals whose last name starts with the word “Fall” that were victimized by an event known as the VUE or the Violent Unknown Event. It’s told in a deadpan mock documentary style with numerous narrators, has a strange narrative current that somehow ties these characters together, can be seen as a mutated sequel to Alfred Hitchcock’s THE BIRDS, and boasts a playful score from Michael Nyman to wrap it all together.

Manic and mechanical, THE FALLS keeps you in focus with its absurdities and allows you to to solve the encyclopedic mystery with comic redundancies and run-ons. Indulgent in the best way possible, it’s truly mad in execution and in thought.

GO DOWN DEATH

Dir. Aaron Schimberg, 2013

USA, 87 min.

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 4 – 7:30 PM

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 10 – 10 PM

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 14 – 7:30 PM

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 19 – 10 PM

Spectacle is pleased to present Aaron Schimberg’s staggering debut feature GO DOWN DEATH. Acclaimed as one of the most distinctive and visually stunning films of the past year, it sits uneasily among rote indie festival programming. Naturally, we feel we make a great pair.

GO DOWN DEATH is a wry, sinister realization of a strange new universe, a cross-episodic melange of macabre folktales supposedly penned by the fictitious writer Jonathan Mallory Sinus. An abandoned warehouse in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, stands in for a decrepit village haunted by ghosts, superstition, and disease, while threatening to buckle under rumblings of the apocalypse. Soldiers are lost and found in endless woods, a child gravedigger is menaced by a shape-shifting physician, a syphilitic john bares all to a young prostitute, and a disfigured outcast yearns for the affections of a tone-deaf cabaret singer. Highlighted by offbeat narrative construction, stunning black-and-white 16mm cinematography, and immaculately detailed production design, GO DOWN DEATH is a distinctively original film informed by American Gothic, folk culture, and outsider art.

Distributed by Factory 25

GOODBYE UNCLE TOM

Dir. Gualtiero Jacopetti & Franco Prosperi, 1971

USA, 135 min. Director’s Cut.

In Italian with English subtitles.

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 4 – 10 PM

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 13 – 7:30 PM

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 17 – 10 PM

MONDAY, DECEMBER 22 – 10 PM

Rarely seen Director’s Cut featuring contemporary documentary footage and original narration. Part of the Mondo America series. Special thanks to Bill Lustig and Blue Underground.

Few films have the mixed legacy accorded to MONDO CANE, the first film by Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi. The box office smash was nominated for the Palme d’Or and nearly won an Oscar for Riz Ortolani’s song “More,” which became a staple at weddings. It invented it’s own dubious genre, shock anthropology, and transformed the common Italian word for “world,” mondo, into a neologism conjuring all that’s bizarre, outrageous, and stranger than the fiction it questionably purports not to be. It’s the international signifier for extreme international weird.

When critics caught up with the put-on, they were relentless in their assault on the duo. By the time they released AFRICA ADDIO, a lurid chronicle of violence in the wake of decolonization in Tanzania and Kenya, they were accused of every kind of ethical violation from flagrant racism to paying soldiers to murder people before their cameras. The duo was hurt, and felt they had to do something to dispel accusations of intolerance.

So they made GOODBYE UNCLE TOM — one of the most challenging, notorious, anti-American, and maligned films of all time.

At a glance, it has very little to do with mondo. Allegedly, the idea took root when Jacopetti suggested the duo make MANDINGO into a documentary — this being many years before Richard Fleischer’s own scintilating Hollywood adaptation. The result is like if Peter Watkins and Ken Russell adapted Kyle Onstott’s taboo-shattering pulp novel about slave breeding and deciding to drive the historically rooted horrors of slavery home further by cranking them up a notch.

Making the tongue-in-cheek claim of being an actual documentary about American slavery, the film charts the entire institution of slavery from arrival (it is widely acknowledged as being the first movie ever set significantly on a slave ship) through supposed emancipation. Pulling many of the least pleasant historical realities of American slavery out from under the rug and rendering them in unhinged expressionistic extremes, it presents the institution as a grotesque atrocity exhibition including rape, infanticide, bizarre medical experimentation, and even a Bathory-esque blood bathing. And it’s all framed with contemporary newsreel footage of present-day civil rights violations and quotes—many of them presented with wry-self critique—from leaders or controversial figures including Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver, and Amiri Baraka, resulting in what Pauline Kael called “the most specific and rabid incitement of the race war” (while acknowledging that people of color seem to appreciate it much more than herself).

Or as Roger Ebert wrote, “They have finally done it: Made the most disgusting, contemptuous insult to decency ever to masquerade as a documentary.” Yet to be fair, one might point out that the “mockumentary” genre the film pioneers—Watkins is the only filmmaker who comes to mind who previously described such a patently fabricated scenario, i.e., one taking place before motion picture cameras were invented, as a “documentary”—was still an almost totally unfamiliar lexicon.

And with that barefaced claim, few movies are as gleefully, sadistically fixed upon a program of not-giving-a-fuck — which one might recognize as a front for a genuine core of outrage. It predates Pasolini’s canonical SALO, a like-minded piece of shock as an instrument of anti-bourgeois (an aim for which its privileged critical positioning might indicate it has failed), but is explicitly linked to the contemporary reality of American racism. Richard Corliss shouts out GOODBYE UNCLE TOM in his positive review of 12 YEARS A SLAVE — and yet one could not leverage the criticism that many, including Kareem Abdul Jabbar, made of 12 YEARS: that it stirs a rage that is compartmentalized into the past and portrayed as history without an acknowledgement of the human motivations that allow slavery to continue to exist around the world. Conversely, GOODBYE UNCLE TOM concludes with documentary footage of peaceful black protesters being brutalized by the national guard, followed by happy-go-lucky Southern Civil War re-enactors who restage history with an outrageously apparent disregard for the complexity and human debasement it represents. As the Italian narrator happily intones on the final line of the film, “It’s wonderful to return home on this splendid day in May and take a nice shower to wash away the past.”

Of course, part of the trouble of GOODBYE UNCLE TOM is that we can’t simply settle upon a simple, revisionist attitude. It’s undeniably an unpleasant, problematic, and troubling film—but one worth revisiting for those willing to confront tangled knots of history and their representation on screen.

HEAD AGAINST THE WALL

aka La Tete Contre Les Murs

Dir. Georges Franju, 1959

France, 95 min.

In French with English subtitles.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 4 – 7:30 PM

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 14 – 7:30PM

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29 – 10PM

Part of the Views from the Inside series from 2014 and reappearing alone in September 2016 as Best of Best of Spectacle.

Anouk Aimee. Charles Aznavour. A shimmering black motorcycle jacket. Georges Franju’s HEAD AGAINST THE WALL taps into cinema’s inherent attractions but renders its own utterly untenable, less a cautionary tale than a smoldering portrait of loss. Behind the gates of a countryside sanitorium lives young Francois (future filmmaker Jean-Pierre Mocky), the hotheaded son of a stuffy lawyer – a wild one in the Brando tradition on the outside, bored to sedation within. Francois knows he’s sane, but while waiting for this latest convulsion of The System to pass, all he can do is look at the people around him – and now, without the comfort of his on-and-off girlfriend Stéphanie (Aimee), his visage isn’t pretty.

Blessed with the same magisterial stillness and dark beauty that gave EYES WITHOUT A FACE its inimitable power, Franju’s feature debut is both straightforward and serpentine. The screenplay (adapted from a Herve Bazin novel) posits man’s place in society as anything but certain; as Francois seeks validation from parties neutral to his domineering father, his individuality seems to vanish. What develops is not a critique of doctors or hospitals, but instead of French paternalism at large. Under the heel of a society founded on class expectations, Francois doesn’t lose his freedom so much as he realizes it never existed in the first place.

“He seeks the madness behind reality because it is for him the only way to rediscover the true face of reality behind this madness… Let us say that Franju demonstrates the necessity of Surrealism if one considers it as a pilgrimage to the sources. And Head Against The Wall proves that he is right.” – Jean-Luc Godard, Cahiers du Cinema

“Whether it’s the weird, eerily erotic gaze of a female inmate or a strange gathering of doves or a cityscape by night that seems as dank and claustrophobic as the asylum walls themselves, Franju’s mastery and palpable adoration of effect is ever evident.” – Glenn Kenny, The Auteurs

HOPE

aka Umut

Dir. Yılmaz Güney, 1970

Turkey, 100 min.

In Turkish with new English subtitles by Spectacle.

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 2 – 7:30 PM

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 7 – 5 PM

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 13 – 10 PM

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 17 – 7:30 PM

Part of the Yılmaz Güney: The Indomitable South series.

HOPE is considered a landmark in the history of Turkish cinema. Güney called it an “epic of verité” due to its break with the conventions of Turkish commercial cinema, the gleaming sets and powdered starlets typical of Yeşilçam (the Turkish Hollywood). Although it is often compared to De Sica’s BICYCLE THIEVES, HOPE also has much in common with Glauber Rocha’s BLACK GOD, WHITE DEVIL—with its rural merchant protagonist who gets fleeced one too many times and turns to a messianic preacher for guidance—and with Ousmane Sembene’s BOROM SARRET, the tale of a poor horse-cart driver in Dakar getting kicked around by the law.

Güney’s character, Cabbar, drives a horse-driven cart in Istanbul. Business is bad, and the rapidly modernizing city leaves little room for a man who uses such quaintly obsolete means to earn his living. His wife, mother, and five children depend on him, and their domestic life is characterized by constant threats and abuse. Indebted to everyone he knows, Cabbar’s fate is sealed when a bourgeois asshole in a sports car mows down one of his parked horses. Unable to borrow more money to replace it or even pay back his existing debts, Cabbar tries his luck at the lottery, then turns to armed robbery. Unfortunately, the American tourist he and his friend try to hold up fails to understand their threats and chases them away in anger. Furious at his creditors and indifferent to other cart drivers’ efforts to organize in a union, Cabbar falls under the influence of a hodja, a kind of wise-man witch-doctor, who promises him buried riches. Cabbar and his friend sever their bonds to the city and join the hodja in a clearly insane quest for treasure hidden in the surrounding desert.

Although it is often interpreted as a critique of the backwards superstitions rampant among the uneducated Turkish proletariat, HOPE should be read instead as a revolutionary call to break with old forms of organizing (whether in the family or in labor unions) and to embrace a non-instrumental form-of-life. It is a manifesto for the abolition of homo economicus and for the reenchantment of the world.

IN A GLASS CAGE

aka Tras el cristal

Dir. Agustí Villaronga, 1986

Spain, 111 min.

In Spanish with English subtitles.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 3 – 10 PM

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 7 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, DECEMBER 15 – 10 PM

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 19 – 7:30 PM

A huge thanks to Nico B. from Cult Epics.

[Trigger Warning: Sustained, recurring scenes of torture and sexual abuse—frequently involving children—presented in harsh, unsparing tones with a palpable, fascist historical context.]

A deeply unnerving film situated in the middle of a variety of genre film lineages, Agustí Villaronga‘s IN A GLASS CAGE blends morose, art-house chamber drama with psychologically-challenging giallo horror and unflinching exploitation film brutality into a force of will that will likely plant itself in your mind forever.

The narrative is historically-weighted yet mostly hedged in back-story. Death-camp Nazi doctor Klaus (Günter Meisner) flees to Spain after the Holocaust, where the emotional toll of his systemic, compulsive physical and sexual abuse of children during and after the war leaves him suicidal. A botched attempt lands him immobilized in an iron lung, cared for by his tormented wife Griselda (Marisa Paredes) and innocent young daughter Rena (Gisela Echevarria). Soon, a strange and aggressive man (David Sust) arrives and takes control of Klaus’ care… at the elder man’s insistence.

Inspired by the notorious, prolific 15th century child-killer Gilles de Rais, Villaronga immediately tapped Günter Meisner (multiple-time Adolf Hitler, Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory) for the role of Klaus, but the actor refused, disgusted with the content of the film. Eventually, he relented, claiming—apocryphally—that he could not get the script out of his mind. Meisner himself had been in a Nazi death camp as a youth.

This marked the first film for Catalan writer/director Agustí Villaronga, who would go on direct Black Bread (2010), winner of numerous Gaudí and Goya awards and the first Catalan-language film to be shortlisted for the Oscars.

Original poster designed by Preston Spurlock.

LIQUID SKY

Dir. Slava Tsukerman, 1982

USA, 112 min.

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5 – 10 PM

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 9 – 7:30 PM

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 23 – 10 PM

[Trigger Warning: Graphic sexual violence and drug use.]

Spectacle is honored to present the unforgettable cult classic LIQUID SKY—the story of a weekend in New York’s hyperrealist, queer, neon, drug fueled, dangerous, and dystopian 1980s featuring cast of underground models, electroclash singers, shrimp-obsessed housewives, scumbag clubbers, addicts, necrophiliacs, and a German Ufologist. Deadpan humor and eroticism, satire and horror, camp and realism make LIQUID SKY several bolts of lightning striking the same bottle.

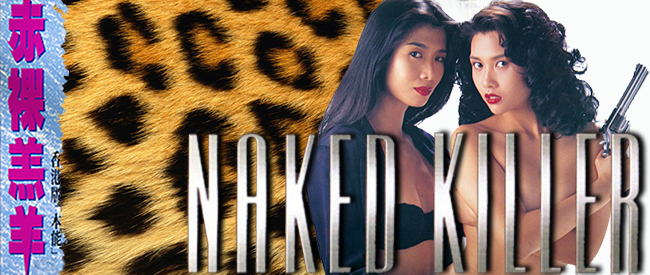

NAKED KILLER

Dir. Clarence Fok Yiu-leung, 1992

Hong Kong, 93 min.

In Cantonese with English subtitles.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 3 – 7:30 PM

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 6 – 10 PM

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 11 – 10 PM

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 16 – 10 PM

Part of the Far East Femmes with Firearms series.

A gleefully sleazy, over-the-top CAT III camp romp about dueling lesbian contract killers and the impotent policeman caught in the middle, NAKED KILLER is a joyous ode to all things (s)excessive.

Following a traumatic crime bust gone awry, Hong Kong cop Taninan can’t seem to perform in the line of duty or in the bedroom… until he meets the enchanting seductress/killer Kitty. Their tango is soon cut short by Sister Candy, a veteran assassin who snatches Kitty away and teaches her the ways of professional execution and how to tap into her sensual side. Almost just as quick, two of Sister Candy’s previous students show up to murder their former teacher, prompting an all-out lesbian assassin war.

With tongue planted firmly in-cheek, director Fok Yiu Leung crosses titillating eroticism with a strong sociological undercurrent denouncing male piggishness. But he also knows how to entertain, and wildly so: copious amounts of milk drinking, dick slicing, office shoot-’em-ups, underwater knife fights, and Skinemax soft-core lesbian playfulness all wrapped up in a engrossing amount of 90s neon bliss… it’s all here and then some.

This is the 1992 summer action blockbuster you deserve.

“Imagine the erotic world of Basic Instinct exaggerated into a kung-fu cartoon of sexy lesbian avengers executing quadruple leaping somersaults in a deadly assault against the opposite sex.” -The New York Times

“John Woo on acid… Naked Killer breaks Mach 5 within the first 10 minutes and never lets up. Bursting with colorful lighting, angles, and set pieces, it’s a panoply of Nineties sex and violence, decadence for decadence’s sake, with little moralizing thrown in. A genuine crowd-pleaser…” -The Austin Chronicle

“It’s like nothing you’ve ever seen before… a stylized girlie graphic novelization of psycho hot babe killers as channeled through and re-imagined by Quentin Tarantino… Naked Killer is girl power gone gonzo, a geek’s wet dream doused with libido lightening messages about Chinese society’s misogyny.” -Pop Matters

WHO’S SINGIN’ OVER THERE?

WHO’S SINGIN’ OVER THERE?

Dir. Slobodan Šijan, 1980.

SFR Yugoslavia, 86 min.

In Serbian with original English subtitles by Spectacle.

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, DECEMBER 8 – 10 PM

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 16 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, DECEMBER 22 – 7:30 PM

Based on an original screenplay by Kovačević. Part of the Three Yugoslavian Comedies by Dušan Kovačević series.

This highly quotable classic, which screened Un Certain Regard at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival, charts the journey of a ramshackle bus across the Yugoslavian countryside toward Belgrade on April 5, 1941. Lorded over by an impetuous conductor and his numbskull son, the passengers constitute a vertiable ship of fools, misfists, and outcasts: among them a disgruntled WWI vet, a goofy hunter, a fatalistic consumptive, libidinous newlyweds, a suave pop singer, and a pair of young gypsy musicians — the source of pointed social tensions — whose folk numbers provide the film’s Greek chorus.

A prime example of the Aristotelian Unities in screenwriting, it follows the little scrapheap-that-could through encounters with highwaymen, funerals, soldiers, and other odd situations, rolling inexorably toward an unexpectedly resonant conclusion.

Fondly remembered to this day, WHO’S SINGIN’ OVER THERE? was declared by the Yugoslavian Board of the Academy of Film Art and Science (AFUN) to be the best Yugoslavian film made between 1947 and 1995.

BACK STREET JANE

BACK STREET JANE WEREWOLF IN A GIRLS DORMITORY

WEREWOLF IN A GIRLS DORMITORY

LASER MISSION

LASER MISSION

WHO’S SINGIN’ OVER THERE?

WHO’S SINGIN’ OVER THERE?