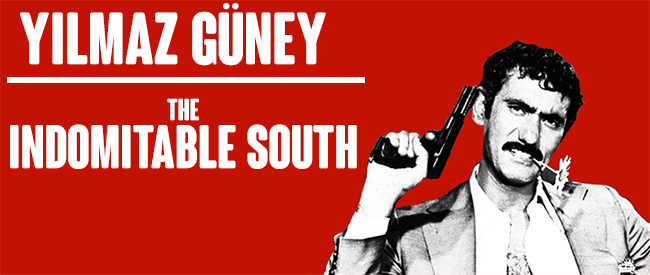

“I am a man of struggle and my cinema is the cinema of the liberation struggle of my people.” -Yılmaz Güney

Critics are fond of separating a filmmaker’s “life” from his “work,” as if the two were related but autonomous spheres. In the case of Yılmaz Güney, the hollow-cheeked, mustachioed action movie star and director whose name has become legend in Turkey, it is clear to everyone that the two are inseparable. A communist Kurd, Güney was looked upon with an unfriendly eye by three successive military regimes in Turkey and spent twelve of his 26 years as a filmmaker behind bars. Many of his films are set in prisons, and when they’re not, his characters are imprisoned by a variety of operations, such as the industrialization of Turkey’s countryside and the proletarianization of its rural nomadic tribes. Constantly hounded by the authorities for his communist “sympathies” while also hugely popular, Güney was a real threat that refused to be neutralized.

Having become an icon by appearing in seventy to eighty films in the 1960s—mostly bloody low-budget revenge movies, shot within days and often based on popular Hollywood movies like ONE-EYED JACKS and I DIED A THOUSAND TIMES— Güney had developed a considerable following by the time he started directing his own films. As critic Atilla Dorsay has said, “His films are watched with as much attention and ‘respect’ as a religious ceremony. The audience is humiliated with him, suffers with him, and when, finally, he decides to revolt, they approve with applause and shouts of joy.” When he turned to analyzing class injustice in HOPE (Umut) in 1970, it was a major shift in affective register. Whereas Güney’s character in THE BRIDE OF THE EARTH from two years previously was a mix of the Man with No Name, Antonio das Mortes, and the T-1000, a near-indestructible vigilante who follows only the law of the gun, his character in HOPE is more like Antonio from BICYCLE THIEVES. What the physician-pedagogue in Truffaut’s THE WILD CHILD says about the boy savage applies equally to this transformation in Güney’s on-screen persona: “What he’ll lose in strength he’ll gain in sensitivity.”

Güney was imprisoned for eighteen months shortly after the military coup of 1960 for a short story he had written as a teenager that constituted “communist propaganda.” The production of THE POOR ONES was cut short when Güney was imprisoned again after another military coup in 1971, this time for sheltering anarchist students. After a general amnesty resulted in his release in 1974, he directed THE FRIEND, widely considered his most nuanced examination of class dynamics in Turkey, and started work on ANXIETY, when he was once again convicted, this time for murdering a conservative judge in a bar fight. Güney would remain behind bars until 1981, but for several years his fame guaranteed him a relatively high degree of freedom in prison. He sent scripts and storyboards to his assistants Serif Gören and Zeki Ökten, who then directed THE HERD, THE ENEMY, and YOL (The Road/The Way) using Güney’s instructions. After yet another military coup in 1980, further repression of all leftist intellectuals severely restricted Güney’s prison conditions, and he escaped to Switzerland. He finished YOL, went to Cannes to collect his Palme d’Or for it with Interpol on his trail, then retreated to Paris. He made one more film, THE WALL, before he died of stomach cancer in 1984.

Güney has described his work as “a refusal of injustice, a call to resistance, the need for organization and also the idea that individual liberation does not make sense, that it does not lead anywhere.” It ranges stylistically from Westerns to social realism, with elements of Godard, B-class gangster movies, and animist mysticism. Though his later films are his most lauded—his penultimate film YOL being the most often screened in the US—his earlier revenge films were both more appealing to the masses and more confident in the ability of the oppressed to collect the strength to kill their enemies. The first half of this eight-film retrospective highlights Güney’s early work as a director, from the Westerns THE BRIDE OF THE EARTH and THE HUNGRY WOLVES to the American-cultural-imperialism-mocking PRIVATE OSMAN and the neorealist-inflected HOPE.

THE BRIDE OF THE EARTH

a.k.a. Seyyit Han

Dir. Yılmaz Güney, 1968

Turkey, 81 min.

In Turkish with new English subtitles by Spectacle

SUNDAY, JUNE 1 – 5 PM

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 11 – 10 PM

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 18 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, JUNE 30 – 10 PM

After making his directorial debut with HORSE, WOMAN, GUN in 1966 and establishing his own production company, Güney Filmcilik, in 1968, Güney made THE BRIDE OF THE EARTH, a tale of love and revenge that brings together the gun-slinging virtuosity of the Ugly King and the plight of the backwards Turkish peasantry.

The stone-faced Seyyit Han has a sweetheart waiting for him in his home village. Years ago, reluctant to condemn her to a life of hardship, he set out to kill all his enemies and promised to return for her. Now, after a seven-year prison sentence, Han returns to find a wedding in progress: his bride-to-be has been promised to a prominent man in the village by her impatient brother. Han’s bitterness and his bride’s suicidal despondency culminate in her tragic death and Han’s vengeance, which he exacts by becoming an inexorable killing machine fueled by his hurt pride, taking out the groom and his henchmen one by one.

THE BRIDE OF THE EARTH dramatizes the subjugation of women through the feudal marriage practices of rural Turkey by cloaking it in a pulse-pounding pseudo-Western shoot-em-up that satisfies our craving for sub-proletarian justice. It is widely considered the first film with Kurdish main characters and can be read as a metaphor for the struggle of the Kurds against oppressive tribal traditions and Turkish landlords.

THE HUNGRY WOLVES

a.k.a. Aç Kurtlar

Dir. Yılmaz Güney, 1969

Turkey, 85 min.

In Turkish with English subtitles

TUESDAY, JUNE 3 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, JUNE 9 – 10 PM

MONDAY, JUNE 16 – 7:30 PM

A communist Western set in the snowy plains of eastern Anatolia, THE HUNGRY WOLVES follows Memet, a mysterious mercenary played by Güney, as he tracks down bandits and exchanges their heads for rewards. Memet rivals the reticent anti-heroes of Leone and Corbucci with his stone-faced screen presence and his reluctance to talk about anything but money. He patiently outwits all his opponents and takes down ever bigger and more cunning gangs, until his final destruction at the hands of the vengeful military police.

Güney shot the film in Muş, one of the 17 provinces that comprise Turkish Kurdistan, during his military service there. The Turkish title, Aç Kurtlar, almost sounds like ‘aç kürtler,’ meaning ‘hungry Kurds.’ Sure enough, many of the bandits preying on the peasants are Kurds, and the film presents an obvious critique of those tendencies among the Kurdish people that cause it to direct its violence against itself rather than against its real enemy (the Turkish state, capitalism).

Called “an epic of banditry” by a critic at the time of its release, THE HUNGRY WOLVES would be the last in Güney’s series of horse-riding tough-guy pictures, soon to be followed by his more sensitive portrayals of existentially threatened peasants and the urban poor.

PRIVATE OSMAN

a.k.a. Piyade Osman

Dir. Yılmaz Güney, 1970

Turkey, 72 min.

In Turkish with new English subtitles by Spectacle

TUESDAY, JUNE 3 – 10 PM

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 11 – 7:30 PM

SUNDAY, JUNE 15 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, JUNE 23 – 7:30 PM

The strangest entry in Güney’s oeuvre, PRIVATE OSMAN belongs neither with the guns-and-muscle revenge rippers of his first decade in cinema, nor with the sheep-and-tractor social portraits of his last.

The titular character, played by Güney himself, is a hapless photojournalist who has returned from military service and now makes his living in Istanbul by manufacturing spectacular crimes that he and his colleague-girlfriend will then be the first to cover. Constantly ducking from the law, shooting up bars, and starting fights, Osman is a kind of devil-may-care Peter Parker, a Belmondo with a camera. His racket eventually lands him in the thick of a crime syndicate’s real intrigues, and he ends up having to walk more of the walk than he expected. Osman takes on more and more of the traits of Güney’s traditional “Ugly King” persona, culminating in a half-hour long showdown in which many bad guys get shot from impressive distances.

Following less in the footsteps of Italian neorealism than HOPE from the same year and more in those of the French New Wave, PRIVATE OSMAN features a girl and a gun, frenetic cutting, and a mockingly American soundtrack consisting mostly of a few repeated bars of Yankee Doodle. Those interested in class struggle will also find the token band of striking workers, portrayed with a mix of back-slapping familiarity and ironic detachment. Snippets of a union leader’s exhortations are heard and glimpses of torn posters for proletarian street rallies are glimpsed. Both references to the contemporary political situation in Istanbul recall early Godard in their light-handedness.

If BAND OF OUTSIDERS is Godard’s most accessible film, PRIVATE OSMAN is certainly Güney’s.

HOPE

a.k.a. Umut

Dir. Yılmaz Güney, 1970

Turkey, 100 min.

In Turkish with new English subtitles by Spectacle

SUNDAY, JUNE 1 – 7:30 PM

THURSDAY, JUNE 19 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, JUNE 30 – 7:30 PM

HOPE is considered a landmark in the history of Turkish cinema. Güney called it an “epic of verité” due to its break with the conventions of Turkish commercial cinema, the gleaming sets and powdered starlets typical of Yeşilçam (the Turkish Hollywood). Although it is often compared to De Sica’s BICYCLE THIEVES, HOPE also has much in common with Glauber Rocha’s BLACK GOD, WHITE DEVIL—with its rural merchant protagonist who gets fleeced one too many times and turns to a messianic preacher for guidance—and with Ousmane Sembene’s BOROM SARRET, the tale of a poor horse-cart driver in Dakar getting kicked around by the law.

Güney’s character, Cabbar, drives a horse-driven cart in Istanbul. Business is bad, and the rapidly modernizing city leaves little room for a man who uses such quaintly obsolete means to earn his living. His wife, mother, and five children depend on him, and their domestic life is characterized by constant threats and abuse. Indebted to everyone he knows, Cabbar’s fate is sealed when a bourgeois asshole in a sports car mows down one of his parked horses. Unable to borrow more money to replace it or even pay back his existing debts, Cabbar tries his luck at the lottery, then turns to armed robbery. Unfortunately, the American tourist he and his friend try to hold up fails to understand their threats and chases them away in anger. Furious at his creditors and indifferent to other cart drivers’ efforts to organize in a union, Cabbar falls under the influence of a hodja, a kind of wise-man witch-doctor, who promises him buried riches. Cabbar and his friend sever their bonds to the city and join the hodja in a clearly insane quest for treasure hidden in the surrounding desert.

Although it is often interpreted as a critique of the backwards superstitions rampant among the uneducated Turkish proletariat, HOPE should be read instead as a revolutionary call to break with old forms of organizing (whether in the family or in labor unions) and to embrace a non-instrumental form-of-life. It is a manifesto for the abolition of homo economicus and for the reenchantment of the world.