So far, Iranian director Kamran Heidari’s 2012 documentary MY NAME IS NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS is his only film to receive any exposure in the States, and even that has been fairly limited. Hopefully, this series, which presents the New York premiere of his 2014 documentary DINGOMARO and world premiere of his latest, NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS, can help remedy that. Born in 1977 near the city of Shiraz, Heidari began directing films after graduating from college. Parallel to that work, he has built up a substantial body of work as a photographer. The four films included in this series insist on the specificity of Shiraz and the south of Iran. At the same time, they exist in a dialogue that acknowledges national boundaries as well as the power of culture to bypass narrow nationalism. NEGAHDAR JAMALI engages in a complex feedback loop between American and Iranian cinema, while DINGOMARO and, to a lesser extent, NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS show how the power of the African diaspora’s music extends to Iran.

Programmed in collaboration with Steve Erickson. Special thanks to Garineh Nazarian, Maaa Film, and Mehdi Omidvari.

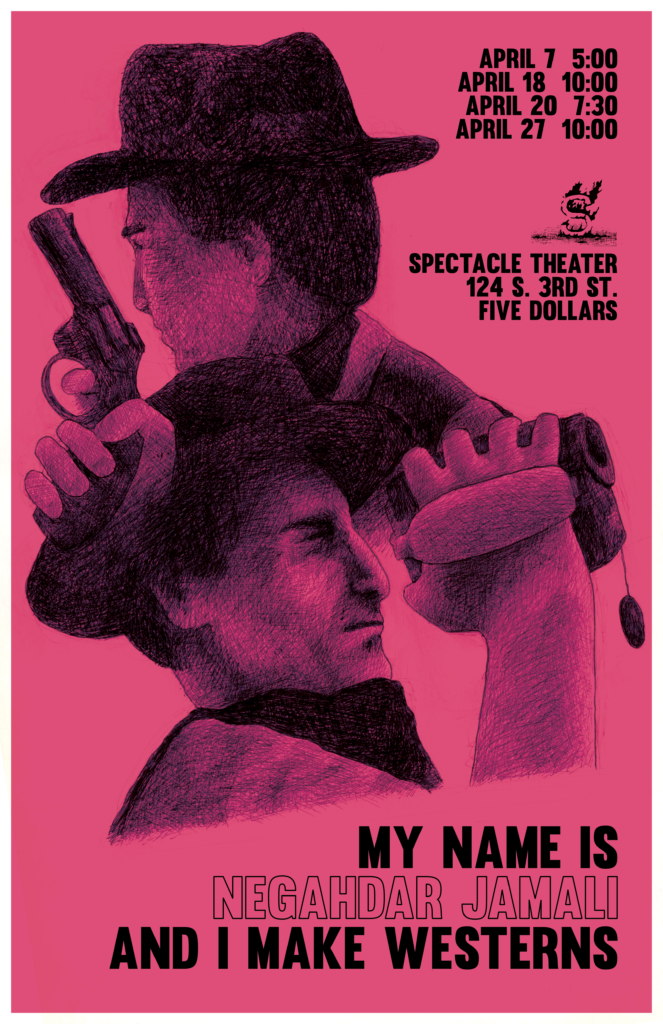

MY NAME IS NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS

(من نگهدار جمالی وسترن میسازم)

dir. Kamran Heidari, 2012

65 minutes. Iran.

In Farsi with English subtitles.

SUNDAY, APRIL 7 – 5 PM

THURSDAY, APRIL 18 – 10 PM

SATURDAY, APRIL 20 – 7:30 PM

SATURDAY, APRIL 27 – 10 PM

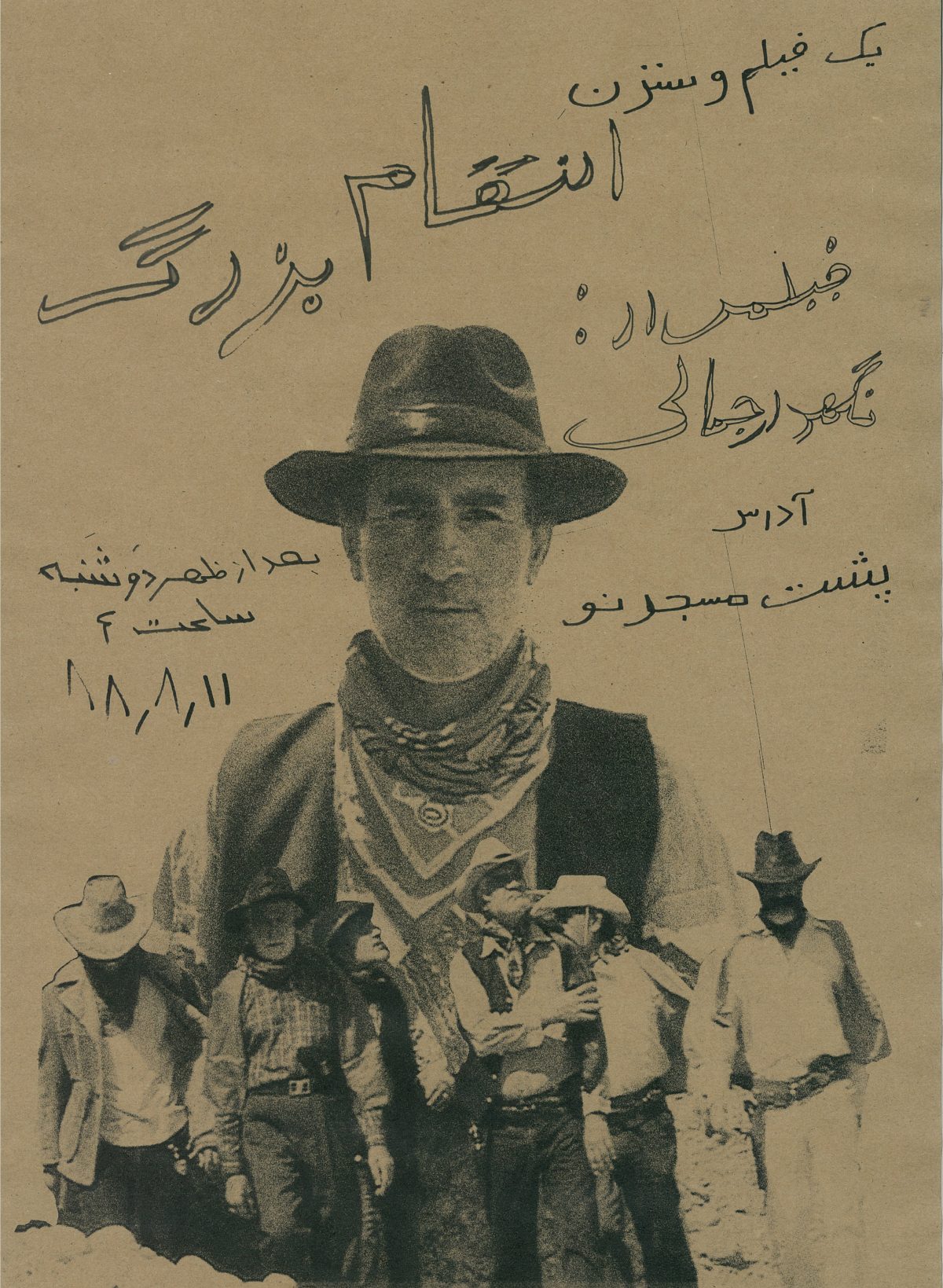

MY NAME IS NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS falls into a tradition of reflexive Iranian movies about filmmaking and directors that includes Abbas Kiarostami’s CLOSE-UP and THROUGH THE OLIVE TREES, Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s SALAAM CINEMA, and A MOMENT OF INNOCENCE, Jafar Panahi’s THE MIRROR and most recently, Mani Haghighi’s PIG. It departs from them in that there’s very little roleplay on Heidari’s part here; the film presents itself as a Western of sorts while always remaining a documentary. MY NAME IS NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS remains upbeat, even celebratory, for its first two thirds, as Jamali buys costumes for his films and talks about his plans to the camera. Then, life intrudes.

Ultimately, MY NAME IS NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS strikes a more ambivalent tone than one would initially expect. Jamali has made a choice between art and his family, and he’s not very kind to his wife and son as a result. Indeed, his son calls Heidari a “fag” and “asshole,” apparently because this documentary’s project has taken so much time away from his father. In the film’s final stretch, Jamali provides pleasure to his community (he holds both rehearsals and screenings in the open air) but winds up as lonely and isolated as many heroes in American Westerns. MY NAME IS NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS ends with an extreme long shot of Jamali riding alone on desert roads, to the tune of Ennio Morricone.

“His {Jamahli’s} minimalism and no-budget, semi- experimental films, like a crossover between the poorest of B westerns and Jack Smith, stands out as ultra primitive drafts of {Budd} Boetticher’s westerns, and, on the other hand, his individualism puts him is the same category as Randolph Scott’s laconic avengers.” – Ehsan Khoshbakht

DINGOMARO

(دینگهمارو)

dir. Kamran Heidari, 2014

66 min. Iran.

In Farsi with English subtitles.

(Note: depicts animal slaughter briefly in the context of a religious ceremony.)

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 3 – 10 PM

THURSDAY, APRIL 11 – 7:30 PM

SUNDAY, APRIL 14 – 5 PM

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 24 – 10 PM

Dingomaro is a wind that sweeps Iran from the African coast. It’s also the nickname of musician Hamid Said, adopted proudly to reflect his African heritage. A population of black Iranians live in the south of the country, having arrived both from voluntary immigration and slavery, but they’ve been almost entirely absent in the country’s arthouse films. (The recent HENDI AND HORMOZ, which played the Iranian Film Festival NY in January, is an exception.)

Heidari films Said, in the wake of his hit “Bad Shans” (“Hard Luck” in English), traveling around the province of Hormozan as he organizes a concert celebrating Afro-Iranian roots. This is his most joyful documentary. Sajjad Avarand’s cinematography – three different cameramen, including Heidari himself, shot the film – captures the region’s immense natural beauty without any of the ironic or melancholic undertones of MY NAME IS NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS. (The two films’ endings rhyme exactly.) It’s a documentary that Jonathan Demme could have made.

However, it doesn’t focus wholly on music, never playing a song all the way through. As cheerful as it is, it’s not without drama, stemming from tension within families. But that gets defused at a father-son concert mixing hip-hop with older forms of Iranian pop. Racism is never expressed overtly in DINGOMARO, but the invisibility of black Iranian identity bites at Said. It’s the reason why he thinks his heritage needs to be explicitly pointed out and celebrated. When he meets up with his friend and fellow musician Carlos Nejad, Carlos says “our younger generation doesn’t even accept that they have African roots… I don’t even know why insist so much that you’re African.” While music is the main means by which DINGOMARO’s subjects assert their blackness, the film also shows ceremonies of the Zar sect, which mixes Shia Islam and indigenous African traditions in a manner akin to Santeria.

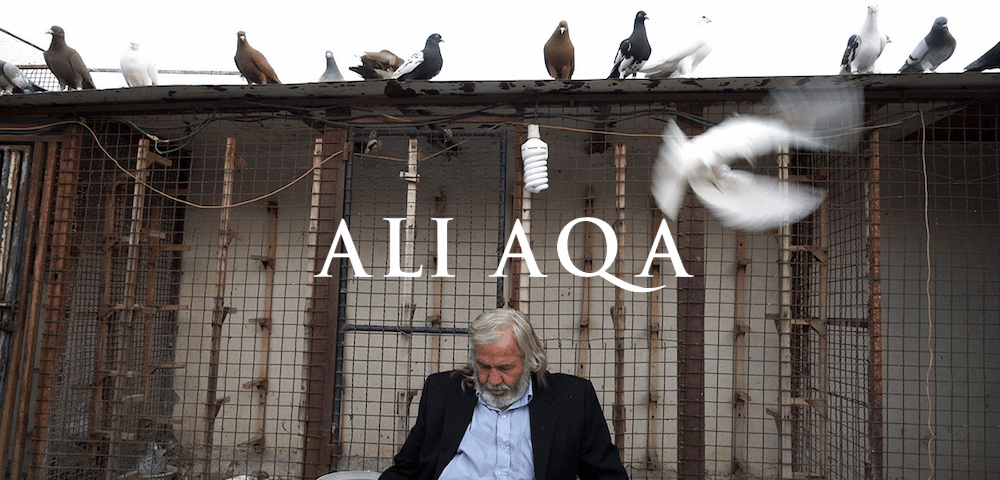

ALI AQA

(علی آقا)

dir. Kamran Heidari, 2017

82 mins. Iran/France/Switzerland.

In Farsi with English subtitles.

THURSDAY, APRIL 4 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, APRIL 15 – 7:30 PM

FRIDAY, APRIL 19 – 10 PM

SUNDAY APRIL 28 – 5 PM

Around the 45-minute mark, something happens which alters one’s perception of Ali: he goes from being a grumpy old man to a danger to the people around him. And while Heidari obviously isn’t a passive observer, Ali and his wife show their awareness of the camera. The film becomes a reflection on the responsibility of documentarians towards their subjects. On the website of the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, Heidari revealed to Mark Baker that “Ali told us not to meddle with his personal life ever again, and even banned us from visiting his home for a while. But after some discussion with him, everything got back to normal and we resumed shooting.” A key moment is edited from the film, although after one has seen it, it’s quite clear what has happened. With this film, Heidari put his body (and camera) on the line in a way that raises the stakes considerably from the friendlier subjects of I AM NEGHADAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS and DINGOMARO.

ALI AQA evolved from Heidari’s interest in photographing pigeons. The project started out as a documentary about them, but he settled on depicting men who love the birds instead. While it respects Ali’s passion, one watches in dismay as the film reveals his enthusiasm devolving from a healthy hobby to something that detracts from his attention to his family. If I AM NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS had a similar underlying drama, ALI AQA raises it to the level of overt critique. But it makes one understand that Ali is trying to find something therapeutic in his pigeons that he can’t get from people, even if this is a largely failed quest.

NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS

(واکس چه)

dir. Kamran Heidari, 2019

67 mins. Iran.

In Farsi with English subtitles.

TUESDAY, APRIL 2 – 7:30 PM

TUESDAY, APRIL 16 – 7:30 PM followed by a Skype Q&A with Kamran Heidari

THURSDAY, APRIL 25 – 7:30 PM

NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS is named after a song by Ibrahim Monsefi, which gets played in several versions during the film. Near the end, its narrator says “how I lived and died is up to me.” Nevertheless, this fictional autobiography tries to reconstruct his life without turning it into a conventional narrative. The film begins with images of the skyscrapers of Bandar Abbas, the city where he was born, taken from a drone. Most of it consists of drifting camera movements, relying heavily on drones, that try to capture the perspective of a person walking slowly while high on heroin. Monsefi died of an overdose of that drug, possibly deliberately. After descending from the sky, the camera takes us to the room where he died.

Heidari and two other screenwriters created a voice-over told by the dead Monsefi. He starts the film by taking about his early life, bringing us to his childhood home and the Hindu temples where he first got a taste of the power of music. As the camera travels around Bandar Abbas, musicians perform Monsefi’s songs in the city’s streets. (It’s reminiscent of the great Brazilian singer/songwriter Caetano Veloso.) While not overtly concerned with race in the same way as DINGOMARO, NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS still showcases the diversity of Southern Iran, emphasizing the coexistence of Islam and Hinduism and the presence of black Iranians.

Mixing elements of fiction and documentary, it tells the story of Monsefi’s life. If the voice-over moves ahead in a fairly linear manner, the images rarely simply illustrate his biography. Instead, the film takes many detours to enjoy the street life of Bandar Abbas and the pleasure of listening to Monsefi’s music. Real and fictional stories of musicians whose early promise – at his peak, Monsefi wrote poetry and acted in addition to his songwriting – vanishes in a haze of drugs may be very common, but NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS is formally unconventional enough that it never feels remotely like a BEHIND THE MUSIC episode. It uses home movie footage gingerly, but its most powerful moment is the ending, where a grainy video of Monsefi performing the title song disappears into flickering electronic snow.

STEVE ERICKSON is a film and music critic who writes for Gay City News, Cineaste, the Nashville Scene, Studio Daily and Kinoscope. He has written and directed 6 short films. His first foray into film programming was Anthology Film Archives’ Mehrdad Oskouei retrospective in February 2018.

KAMRAN HEIDARI was born in Gachsaran, near Shiraz, in 1977. He is a freelance documentary filmmaker and photographer, with an interest in street photography, graffiti and ethno-music. His work focuses on film and photography about the people of Shiraz (Fars Province) and the South of Iran. MY NAME IS NEGAHDAR JAMALI AND I MAKE WESTERNS was screened at many festivals around the world, including the 2013 Busan International Film Festival and Rotterdam.